Automobile & Transportation

EV Charging Equipment: Coverage Expansion and Upgrading Drive US$55B by 2032

04 February 2026

February 4, 2026—APO Research’s 2026 study indicates that the global EV charging equipment market (measured on a production-value basis) reached about US$ 10.2 billion in 2025 and is expected to rise to roughly US$ 12.8 billion in 2026. Looking beyond the current 2030 forecast window, production value is projected to approach US$ 55 billion by 2032, implying a 2026–2032 CAGR of approximately 27%. In unit terms, global output increased to about 4.8 million units in 2025 and is forecast at around 6.3 million units in 2026; by 2032, annual production is expected to reach roughly 28 million units, reflecting continued scale-up but with a visible post-2030 normalization in growth rates as leading markets mature and grid constraints become binding in more geographies.

EV Charging Equipment (often referred to as EVSE, Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment) is the integrated hardware-and-control system that safely delivers electrical energy from the grid or an on-site power source to an electric vehicle, manages the charging session through standardized signaling and communications, and enforces electrical protection, metering, and user or network control required for public or private operation. It spans AC charging equipment that supplies regulated AC power to the vehicle’s on-board charger (typical residential and workplace use) and DC charging equipment (DC fast chargers) that performs off-board AC-DC conversion and delivers controlled high-voltage DC directly to the vehicle battery via the vehicle’s battery management system interface, with performance defined by output power, voltage-current envelope, conversion efficiency, uptime, thermal limits, and compliance with electrical safety and interoperability standards.

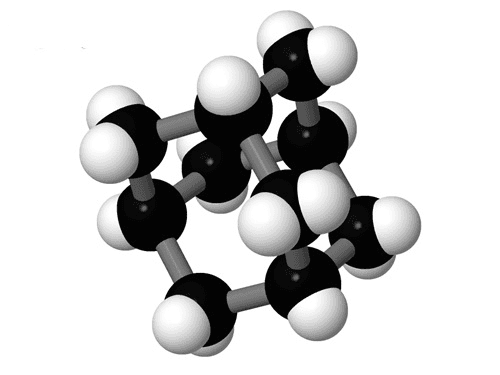

From a materials and hardware standpoint, EV charging equipment is a power-electronics and electromechanical assembly built around high-current conductors and robust insulation systems. Core elements typically include input protection and switching (breakers, contactors, surge protection), metering and sensing (current shunts or Hall sensors, voltage sensing, temperature sensors), control electronics (MCU/SoC, safety monitoring, communications modules), and the energy transfer interface (charging cable, connector, and vehicle inlet coupling). DC chargers add rectification and conversion stages (PFC front-end, isolated DC-DC modules), magnetics (inductors/transformers), DC bus capacitors, and more demanding thermal management. Common material sets include copper or copper alloys for busbars and cable conductors; aluminum for heat sinks and structural enclosures; engineering plastics (PC, PC-ABS, PA) and elastomers (EPDM, silicone) for housings, seals, and strain relief; flame-retardant insulating laminates on PCBs; ferrites and laminated steels for magnetics; and protective coatings, potting compounds, and conformal coatings to control corrosion, moisture ingress, partial discharge risk, and long-term dielectric integrity in outdoor environments.

Process-wise, EV charging equipment executes a controlled energy-delivery workflow rather than acting as a passive “power outlet.” It performs connector state detection and interlock management, establishes a charge session through pilot/proximity signaling and higher-level communication protocols where applicable, negotiates allowable voltage/current/power with the vehicle, and modulates output under closed-loop control while monitoring fault conditions (ground fault, overcurrent, overvoltage, overtemperature, insulation and leakage, connector overheating, arc risk). Networked chargers add authentication, tariffing, session logging, remote diagnostics, load management (including site-level power sharing), and firmware/cybersecurity lifecycle controls. Interoperability is achieved through established interface families (regional connector systems and signaling/communications stacks) and through backend integration for public charging, roaming, and fleet operations.

Manufacturing of EV charging equipment combines industrial power electronics production with outdoor-rated electromechanical product engineering. Typical build flows include SMT assembly and testing of control and power PCBs, integration of power modules (IGBT/SiC MOSFET stages for DC chargers where applicable), busbar and harness fabrication with controlled crimping and insulation clearances, enclosure assembly with gasketing and ingress protection, thermal stack assembly (heat sinks, cold plates, fans or liquid loops), and calibrated metering integration. End-of-line validation commonly covers dielectric withstand and insulation resistance, ground-fault functionality, contactor performance, connector temperature sensing, load tests across the rated operating envelope, efficiency checks, EMC screening, environmental sealing verification, and burn-in or stress screens for reliability. Design-for-serviceability and modular replacement (power modules, contactors, communication units, cable assemblies) is a key manufacturability and lifecycle cost driver, especially for high-utilization public DC sites.

In the industry value chain, upstream inputs come from grid and protection component suppliers (switchgear, breakers, SPDs), power semiconductor and passive component ecosystems (devices, magnetics, capacitors), cable and connector manufacturers, thermal management suppliers, enclosure and corrosion-protection systems, and certified metering modules where billing-grade measurement is required. Midstream, EVSE and DC charger OEMs integrate these subsystems into certified products, often with separate lines for residential AC wallboxes, commercial AC pedestals, and modular DC fast-charging cabinets/dispenser architectures, supported by software stacks for device management and interoperability. Downstream, electrical contractors and EPC firms handle site design, permitting, civil works, and commissioning; charging network operators and fleet depots run operations, maintenance, and uptime SLAs; utilities and energy service providers influence interconnection, demand management, and tariffs; and end users (homeowners, workplaces, retail, highway corridors, fleets) drive feature requirements around reliability, total installed cost, charging speed, payment experience, and long-term service support.

The headline growth is not “just more chargers”; it is a mix upgrade story. Value expands faster than installed base because the product mix keeps shifting toward higher-power, higher-content systems: multi-hundred-kW DC fast chargers, liquid-cooled cables, higher-voltage architectures, improved thermal and protection design, and increasingly standardized communications and payment integration at the station level. At the same time, AC charging remains unit-heavy but structurally more price-competitive, with faster commoditization and sharper tender-driven pricing. This divergence matters because it explains why “units” can grow quickly while profit pools concentrate where power electronics content, compliance burden, and field-reliability requirements are highest.

Regionally, the value pool is anchored in China and Europe, with China still the primary scale engine. China is estimated at about US$ 7.3 billion in 2026 (and roughly 3.7 million units), rising to around US$ 23.1 billion by 2030 as public network densification and corridor fast charging continue to absorb large volumes of DC equipment; by 2032, China is likely to sit in the low-to-mid US$ 30 billions on a production-value basis. Europe is expected at around US$ 2.8 billion in 2026 (about 1.3 million units), benefiting from cross-border corridor build-out and stronger public-access requirements; by 2032, Europe plausibly reaches the ~US$ 10–11 billion range. North America is forecast at roughly US$ 1.6 billion in 2026 (around 0.6 million units) and trends toward the high single-digit billions by 2032, with the pace increasingly determined by interconnection timelines, site permitting, and the practical economics of uptime and maintenance rather than by charger hardware availability alone.

By product form, the market is already bifurcated: AC dominates units; DC dominates value. In 2026, AC output is expected to be around 5.2 million units versus DC at roughly 1.1 million units, yet production value is the reverse, with DC at about US$ 9.8 billion and AC at about US$ 3.1 billion. This value concentration is reinforced at the use-case level: public charging (including highway and fleet-access sites) is forecast at roughly US$ 10.5 billion in 2026, versus residential charging at about US$ 2.4 billion, because public sites pull through higher-power equipment and more demanding reliability and compliance requirements; the split remains directionally similar through 2030, even as residential volumes grow steadily and AC pricing continues to compress.

From a manufacturing and value-chain standpoint, EV charging equipment scales like an electro-mechanical power conversion business with a software-operability overlay. Cost and lead times are primarily shaped by power modules and switching devices, magnetics, thermal management, contactors and protection components, connectors and cable assemblies, enclosure and ingress protection design, and factory test capacity (burn-in, high-voltage safety testing, and functional verification). As volumes compound, competitive advantage shifts away from “can you build a charger” toward “can you deliver certified, grid-compatible, serviceable equipment with predictable uptime economics,” which is why long-run growth increasingly depends on standards convergence, service networks, and the ability to re-engineer BOM and thermal design without sacrificing field reliability.